Labour and Social Protection Policies Paper – First Draft

Paper prepared by Naome Chakanya for the National Citizens Convention (NCC) to held on 22-23 August 2019, Harare.

1.0 Introduction: Conceptualising labour (employment) and social protection policies

Labour rights, decent employment and social protection are altogether human rights as enshrined in the various international rights instruments which includes the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR), and the International Labour Organisation (ILO)’s instruments (Conventions) that the Zimbabwean Government have signed to. This means that these three human rights are basic standards without which people cannot live in dignity as human beings. For instance, Article 6 of the ICESCR states that the right to work includes “the right of everyone to the opportunity to gain his living by work” whilst Article 9 of the ICESCR protects “the right of everyone to social security, including social insurance.”

At national level, labour rights, decent work and social protection are all enshrined in the Zimbabwe Constitution. Section 65 of the Constitutions provides for labour rights and decent work whilst Section 24 on work and labour relations implores the state and all institutions and agencies of government at every level to adopt reasonable policies and measures to provide everyone with an opportunity to work in a freely chosen activity, in order to secure a decent living for themselves and their families. This therefore means that the state should adopt pro-labour and pro-employment policies in order for its citizens to enjoy decent work and living standards for themselves and their families. On the other hand, the Constitution Sections 21 and 82 provides for the right to social protection for the elderly whilst Section 30 of the Constitution makes it clear that, “…the state must take all practical measures, within the limits of the resources available to it, to provide social security and social care to those who are in need”. Thus, the basic premise is that these variables are rights and not privileges and the state has the legal obligation to provide, promote and fulfil these rights through appropriate and relevant policies and other measures.

However, whilst the Constitution is very clear on these rights, labour rights, decent employment and social protection deficits are amongst the defining challenges of the Zimbabwean economy. This is despite the existence of the National Employment Policy Framework of 2013 (revised in 2015) and the National Social Protection Strategy Framework of 2015. Whilst these policy frameworks clearly underscored the importance of labour rights and robust social protection systems, they suffer largely from lack of implementation arising from lack of prioritisation by the Government. In many cases, labour issues and social protection are either treated as “add ons”, secondary issues, appendages or marginal issues in the development of macro-economic policies and frameworks and yet these are policies that should be placed at the centre stage as drivers of sustainable and human- centred development.

For most poor people, work is the only asset they have, as well as the primary pathway to escape material and income poverty. Hence, comprehensive labour market policies are critical in lifting the majority of these poor out of poverty.

The National Social Protection Strategy Framework (2015) defines social protection as: “…a set of interventions whose objective is to reduce social and economic risk and vulnerability and alleviate poverty and deprivation”. Such interventions are designed to form a coherent system that promotes equity, resilience, and opportunities for the poor and vulnerable. However, the definition extends beyond poverty alleviation, including issues related to inclusive social and pro-poor economic growth associated with protective, preventive, promotive and transformative interventions that provide social insurance, social assistance, labour market interventions and livelihood support and resilience building interventions (FES and Kanyenze, 2019). Essentially, social protection promotes access to basic social services such as health care as well as income security, particularly in cases of old age, unemployment, sickness, invalidity, work injury, maternity or loss of the main income earner.

However, historical setup of the labour market and social security in Zimbabwe was such that the formal economy workers had access to contributory social protection schemes through their contributions to pensions (public and private) and medical aid schemes. This therefore meant that a formal (wage- and salary-earning) worker had a higher coverage of social protection than a worker in the informal economy or engaged in precarious work (contract or casual work) who had no contribution to traditional contributory national social protection schemes. Hence, the degree of informality and its drivers are relevant pieces of the context, which explains the low levels of social protection in Zimbabwe.

Providentially, over the years, there has been a growing recognition of the intricate relationship between labour and social protection policies and their need to be placed high in the sustainable developmental framework. To illustrate the relationship between labour and social policies, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 1999 developed the Decent Work Agenda (DWA) which is premised on four pillars namely (i) employment creation; (ii) workers’ rights; (iii) social protection; and (iv) social dialogue. These four pillars are “inseparable, interrelated and mutually supportive”, meaning failure to achieve one may lead to failure to achieve the other three pillars. This also means that employment and social protection policies are indispensable routes to socio-economic development, poverty reduction and human dignity, thus sustainable and humane –centred development.

This relationship was further supported by the ILO 2010 Conference report which explicitly stated that:

“there is no trade-off between economic and employment performance on one hand and the development of social security on the other. Social security has a beneficial impact on the economy and the labour market by providing protection for the unemployed, people with disabilities, and elderly and vulnerable groups; smoothing the economic cycle and hence providing a cushion for economic activity and even employment. Another beneficial effect is that social protection policies increase labour productivity, for instance by providing health care and protection against employment-related accidents and occupational diseases. Finally, social services provide an important number of jobs themselves, usually with a high share of female employment.”

Furthermore, the linkage and importance of labour and social protection policies is reinforced by the Global Agenda 2030 (Sustainable Development Goals – SDGs). The promotion of more and decent jobs and comprehensive social protection systems are central elements that cuts across many of the SDGs in particular, SDGs 1, 5, 8 and 10, with SDG 8 being the main SDG in these areas (Table 1).

Thus, the current development policy discourse and debate have placed actions on development of comprehensive employment and social protection policies at the centre stage.

Table 1: SDGs and Targets related to social protection

| SDG No. | Targets related to social protection |

| SDG 1 – End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

|

Target 1.3 – Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable

|

|

Goal 5 – Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls |

Target 5.4 – Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate |

| Goal 8 – Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

|

Target 8.5 – By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value |

| Goal 10. Reduce inequality within and among countries | Target 10.4 – Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality |

Clearly, labour market and social policies have a major impact on the effort to promote inclusive and sustained economic growth (SDG 8) as well as ending poverty in all its forms (SDG 1), gender inequality (SGD 5) and inequalities in general (SDG10). More so, social protection systems also promote gender equality through the adoption of measures to ensure that women who have children enjoy equal opportunities in the labour market. Additionally, the current global developmental discourse underscores that government should view social protection as an investment rather than a cost and by providing a safety net in case of economic crisis, social security serves as a fundamental element of social cohesion, thereby helping to ensure social peace and foster economic development.

2.0 The state of labour and social protection policies in Zimbabwe

2.1. Developments in the labour market, labour policies and measures

There is growing global consensus that it is impossible to look at employment issues without a concern for the quality of the employment (jobs) generated (FES, 2019). Furthermore, the ILO accentuates that the nexus between economic growth and poverty reduction is decent employment. This means that, it is not the quantum of employment created that matters, but the quality and decency of employment, and whether such employment is able to uplift workers out of poverty. Hence any labour policy should be able to address the decency of employment. One of the elements of decency of employment is conditions of work which involves fair treatment in employment, stability and social protection security at work and occupational health and safety. Thus, any job without social protection is not decent work. This reiterates the fact mentioned above that decent work and social protection are inseparable and mutually reinforcing. Poor conditions of work are evidenced by poor morale among working people, shirking, moonlighting, multiple-jobbing, low productivity, high turn-over and corruption, which undermine human development (LEDRIZ, 2016).

For the past two decades, the country has been experiencing structural regression characterized by de-industrialization (job destruction) and informalization of labour and economy. For instance, from 2011 to 2014, a total of 4,160 companies closed, resulting in 55,443 jobs being lost (LEDRIZ, 2016). The worst affected sectors included distribution, hotels and restaurants, agriculture, manufacturing, mining and construction. This was contrary to the promise by the ruling Zanu PF in the election year of 2013 that they would create 2,2 million jobs if it won the elections[1].

The 2014 LFCLS revealed that 94.5% of the persons then currently employed, 15 years and above, were informally employed; up from 84.2% in 2011 and 80% in 2004. A total of 98% of the currently employed youth aged 15-24 years were in informal employment whilst 96% of currently employed youth aged 15-34 years were in informal employment (Sachikonye et al, 2018).

Furthermore, the 17 July 2015 Supreme Court Ruling resulted in more than 20,000 workers losing their jobs in three weeks following the judgement (ZCTU, 2016). Those who lost their jobs had no alternative but to find different sources of livelihood in the informal economy.

Another key feature in the Zimbabwe labour market has been the growing but disappointing trend where permanent employment is quickly being eroded and replaced by contract, part-time, casual and seasonal workers. Hence, the country has been digressing from permanent employment status which is stable to increasing precariousness and worker insecurity. The shift to non-standard forms of employment was also causing serious violation of workers’ rights especially when the gender dimension is factored in. High casualization rates are found in female-dominant sectors such as agriculture, domestic, food, hospitality and the informal economy. Thus, female workers were bearing the brunt of the casualization effects.

Additionally, in March 2019, the average minimum wage in the private sector stood at around ZWL 400, while the least paid in the public sector earned ZWL 488, against a PDL of USD873 in March 2019 (LEDRIZ and FES, 2019). Furthermore, a new wave of loss of value of wages, salaries, pensions and savings emerged since October 2018 associated with rising inflation, which increased from 5 percent in September 2018 to 98% by May 2019 and further to 175.7 percent by June 2019. Food inflation stood at 251.94 percent as at June 2019. Further, the introduction of a mono-currency regime (ZWL) in 2019 has further eroded the nominal wages. Evidently, such “poverty” wages seriously undermine the capacity of workers to provide for their social protection and welfare including for their families.

Apart from the above challenges, wage theft was growing problem for both permanent and non-permanent workers. Wage theft refers to workers not receiving their salaries or getting their wages and salaries in parts. The research undertaken by LEDRIZ in 2015[2] revealed that wage theft had grown to alarming levels as the economic crisis persisted with employers citing viability challenges with some even facing closure without paying outstanding wages and salaries. Given the rise in inflation, the research showed that workers facing wage theft were the biggest losers since inflation would have eroded the value of their money before receiving it. In addition, to wage theft, the research also indicated that most casual workers are not given wages set at the sectoral National Employment Councils (NECs) level, a clear violation of workers’ rights and signs of indecent work.

Whilst the Constitution provides for labour rights, a development that was welcomed by workers and trade unions, enforcement of the labour rights remained a challenge with the judiciary’s interpretation in some fundamental areas becoming a cause of concern (LEDRIZ and FES, 2019).

A cause of concern in the labour market has been serious quest for labour market flexibility (the relaxation of the labour laws). Labour market flexibility has dominated the policy framework since the period of the Government of National Unity (GNU).

For instance, the 2012 National Budget Statement presented by the then Minister of Finance, Tendai Biti proposed ‘…a comprehensive review of the labour legislation with a view of making it flexible and consistent with business realities’. Later, during its re-engagement process with the IMF in June 2013, through the Staff Monitored Programme and Article 1V Consultation, the Government pronounced in its 2014 National Budget Statement the need for labour market flexibility and a policy of linking wages to productivity. This was further buttressed by the Monetary Policy Statements of 2015-16 which called for the need to review the Labour Act to allow more labour flexibility. Since then, the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) has openly resisted the promotion of labour market flexibility because for the worker, labour market flexibility results in denial of labour rights and is associated with low and indecent wages, job insecurity and lack of social protection.

Another development that sought to exercise labour market flexibility was the 2015 Supreme Court Judgement that reasoned that employers had a common law right to terminate a contract of employment and that the current Labour Act had no provision that bared an employer from resorting to common law in terminating an employment contract. The immediate result was the dismissal of over 20,000 workers in period of less than two months (Sachikonye, et al, 2018), although the figures were disputed by the Employers’ Confederation of Zimbabwe (EMCOZ), which put the figure at about 4,800 without any justification (ibid). The judgement resulted in a lot of commotion in the economy and was met by immense criticisms by the labour movement and other economic actors. The ZCTU demanded for the amendment of the Labour Act Chapter 28:01 to stop termination on notice which resulted in the enactment of the Labour Amendment Act No. 15 of 2015 which banned termination on notice and provided that affected workers be given one month’s salary for each two years of service or the equivalent lesser proportion of one month’s salary or wages for a lesser period of service as compensation. The Constitutional Court further ruled in favour of pay compensation in retrospect to the affected workers.

Another development favouring labour market flexibility following this, was the attempt by the Government in 2016 to deny application of the Labour Act in Special Economic Zones. This development was met by massive resistance by the ZCTU. The ZCTU embarked on a campaign to resist the Bill which effected this position and went to the extent of engaging the then President Mugabe who then refused to sign the Bill into law and ordered a revision as demanded by the ZCTU (Sachikonye, et al, 2018).

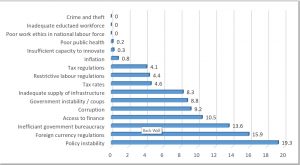

Interestingly and on the contrary, research has proved that labour market regulations are not on top of the list of major constraints doing business in Zimbabwe. Table 2 shows the most problematic factors for doing business

Table 2: The most problematic factors for doing business in Zimbabwe, 2017

Source: World Economic Forum, 2017

Table 2 clearly indicates that labour regulations are not even the top 5 constraints of doing business in Zimbabwe. Labour regulations are ranked 9th out of the 16 factors. Hence, there is need for the government to reconsider labour market flexibility and concentrate on addressing the major constraints against this ranking such as policy instability, foreign currency regulation, government bureaucracy, access to finance, corruption, among others (ZIMCODD, 2018).

In a nutshell, the developments in the labour market and the labour policies and measures pursued in the given period have continued to undermine labour rights including social protection for workers. In fact, the structural regression of the economy has worsened job insecurity and intensified decent work deficits. This has been compounded by lack of adequate labour policy measures and support, seriously undermining the only resource that the poor have, which is their labour, and altogether narrowing the capacity of workers to escape poverty. Overall, labour market flexibility without comprehensive social protection systems in place leads to increased decent work deficits and escalation of poverty.

2.2. Social protection developments and policy measures

This section will focus on social protection as regards labour and social protection in general. It is critical to note that the decimation of social protection in Zimbabwe intensified at the height of the economic crisis in 2008 and has prolonged due to the continued deterioration of the economy. A range of social protection instruments are being implemented in the country namely cash and in-kind transfers, public works programmes, health and education assistance, child protection services, social insurance programmes, and programmes to rebuild resilience and livelihoods. However, despite these interventions, country’s social protection system remains fragmented and duplicative and hence its limited impact on poverty and vulnerability (Sachikonye, et al, 2019). In fact, social protection deficits still abound. For instance, the 2014 Labour Force and Child Labour Survey (LFCLS) revealed that only 2.1 per cent of the population were receiving a monthly pension or some social security funds by 2014. The same Survey also revealed that only 9.4 per cent of the population were members of a medical aid scheme, up from 8 per cent in 2011. Clearly, the majority of the employed and their families, as well as other disadvantaged groups, are excluded from formal social protection coverage.

With weak social protection systems, and erosion of wages and salaries and social security schemes through hyperinflation, remittances provided a buffer for social protection for the majority of Zimbabweans at home, kept households afloat and served as a hedge against complete collapse of families (FES and WLSA, 2019). It is within this context that the country developed the National Social Protection Strategy Framework in 2015 in realisation of the critical role of social protection in socio-economic transformation as well as providing measures to address the collapse of social protection systems in the country.

However, despite the existence of a social protection framework and even under the Zim-Asset document where social protection was highlighted as one of the key components under two clusters namely the Food Security and Nutrition and the Social Services and Poverty Eradication, social protection deficits still exists in practice.

2.2.1. Growth of the informal economy and implications on social protection

The collapse of the formal economy and the unprecedented rise in the informal economy has seriously undermined social security provisions for workers. For instance, the 2012 FinScope Survey revealed high levels of informalisation citing that that 5.7 million people were working in MSMEs, with 2.8 million as business owners and 2.9 million as employees.

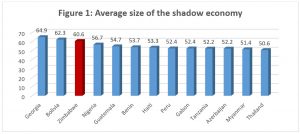

A recent study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on shadow economies (informal economies) in 158 countries revealed that Zimbabwe ranked 3rd with 60.6 per cent after Georgia (64.9 per cent) and Bolivia (62.3 percent) (Figure 1). The study highlighted that Zimbabwe now ranked the first in Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of the average size of the informal economy.

Source: IMF, 2018

Regrettably, workers in the informal economy are at the bottom of the economic and social ladder, working under precarious conditions without access to any form of social protection, with their work suffering from decent work deficits, being casual, ‘unprotected,’ ‘excluded,’ ‘unregistered,’ or ‘unrepresented’ (Sachikonye, et al, 2018). Worryingly, most of those in the informal economy are the youths and without paid permanent employment and social security, the youths in Zimbabwe are becoming stereotyped as the ‘lost generation’ (ibid).

2.2.2. Informalisation of the formal economy and implications on social protection

Over the past years, employment in the formal economy has become increasingly informalised (casual, part-time and contract employment). Informal employment in the formal economy is associated with lack of social security benefits. From a gender perspective, the LFCLS of 2004 to 2014 reveal that women were increasingly over-represented in economic sectors that often have informal employment which lack social security and are more poorly remunerated such as agriculture, distribution, restaurants and hotels, health and private domestic work.

Additionally, the LFCLS from 2004 to 2014 underscores the unprecedented rise in informal employment. The 2014 LFCLS indicated that 94.5 percent of the currently employed persons 15 years and above were informally employed up from 84.2 percent in 2011 and 80 percent in 2004). In terms of the youth dimension, the 2014 LFCLS revealed that 98 percent of the currently employed youth aged 15-24 years and 96 percent of currently employed youth aged 15-34 years were in informal employment. This means that youths have 2 percent chance of getting a formal job.

2.2.3. Economic crisis and impact pensions and social protection in general

The economic crisis which reached its peak in 2008 characterised by hyperinflation and the structural regression thereafter, resulted in the erosion of earnings, pensions and private insurance. As a result, remuneration became meaningless as there was hardly any incentive to work whilst pensions and insurance products were rendered valueless. For example, through the removal of 25 zeros from the currency between August 2006 and February 2009 insurance companies The loss was also accentuated through the removal of 25 zeros from the currency between August 2006 and February 2009 which resulted in and pension funds terminated insurance and pension liabilities without having to pay anything (ibid).

Worse more, the introduction of the multi-currency system in 2009 lacked regulatory guidance and left the conversions of pensions, savings insurance and real investment returns from Zimbabwe Dollar to United States Dollars to the whims of individual service providers (ibid). Consequently, pensions and insurance contributors’ funds, retirement and savings lost value and were prejudiced, and in some cases where arbitrary terminated as was established by the 2015 Commission of Inquiry into the Conversion of Insurance and Pension Values from Zimbabwe Dollars to United States Dollars[3] (ibid).

Additionally, in 2015, the Government through its de-monetisation measures from Zimbabwe Dollars to USD, seven years after used an arbitrary parallel and hence illegal exchange rate of 1USD to 35 quadrillion Zimbabwe dollars (the UN rate) to compensate non-loan bank balances as at 31 December 2008, which resulted in most workers being reimbursed a paltry US$5.68 altogether this entailed “devaluation and debasing of labour.”

Further, the emergence of parallel exchange rates for cash, bond notes, electronic transfers, mobile money, the “controversial” 2 percent transaction tax on mobile money transfers and the attended inflationary pressures renders pensions and insurance funds (which are often deposited into bank accounts) meaningless. For instance, most pensioners receive a paltry ZWL80 per month which translates to only US$8 per month – a serious violation of basic human rights.

2.2.4 Existing economic policy framework, austerity measures and social protection policies

The existing developmental policy document titled “Towards an Upper-Middle Income Economy by 2030-Towards Dispensation Core Values” aptly termed Vision 2030 has a strong neo-liberal as it follows market economy tenets which tend to neglect the people and investment in social policies in pursuit of foreign direct investment (FDI). It is important to note that Zimbabwe has followed this path before under ESAP (1991-1996) and the results were devastating not only at the individual level but also at the national level. The first implementation programme under Vision 2030, Transitional Stabilization Programme (TSP) (October 2018 to December 2020)] and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s Monitored Programme (SMP) both lack a social dimension meaning the fate of the poor is effectively forgotten (Kanyenze, 2019).

In fact, Vision 2030 turns out to be worse off than ESAP, as under ESAP, clear social safety nets were integrated into the programme, whereas under Vision 2030, there are no clear integrated modalities of implementing social protection and safety nets programmes. Essentially means that the policy document is anchored on a neo-liberal approach to development which focuses on a “trickle down” effect to economic growth. Lessons from past policies show that social protection and poverty reduction should not be seen as ‘add ons’ but rather than as an integral component of the policy.

Further, the 2019 National Budget Statement’s theme of “Austerity for Prosperity” based on the expectation that this will bring confidence to markets and investors. Rather than being selective in where cost cutting is needed and where increased spending would be beneficial, the 2019 Budgets Statement interprets austerity as an end in itself without proving how austerity measures will result in achievement of social and economic objectives that the government has set for itself (WLSA, 2019). These austerity measures come at a time when social protection is already under-, and irregularly financed in the National Budget (Box 1). The most critical question is not how much the government is spending, but rather what the government is spending money on.

Box 1: An analysis of national budget allocations to social protection

In the National Social Protection Policy Framework (NSPPF), the target was to consider as eligible for all forms of social assistance in the short to medium term all the 500,000 households which are deemed to be below the Food Poverty Line.

- On the basis of the US$19,298,000 allocated for social welfare in 2018, each household would get a meagre US$38.60 per year and US$70.55 in 2019.

- On the basis of the 415,900 vulnerable children to be reached with educational support as indicated in the Blue Book, the US$23,485,000 allocated to child welfare in 2018 works out at US$56.47 per child per year for 2018, while the US$31,592,000 allocated for child welfare yields a support level of US$75.96 per child per year.

Source: LEDRIZ and FES (2019). Action Research on Social Protection in Post-Independence Zimbabwe, 1980-2019

On the other hand, the Basic Education and Assistance Module (BEAM) also suffers the same fate. In 2018, BEAM received budgetary support of US$20 million for around 416 000 vulnerable and orphaned learners. Simple division indicates each child was getting only US$48 for the year! This lack of social spending means that the State is actually in breach of its own constitution which guarantees the respect of human rights as indicated earlier.

2.2.5 Gender implications of lack of adequate social protection policies

The absence of comprehensive social protection systems and mechanisms has a gendered dimension. This is often due to the gendered social norms that view unpaid care work as a female duty. The deterioration of the socio-economic environment coupled by the austerity measures of the Government and the rollback in the state’s provision for social services and social protection has in turn increased time spent in care and unpaid work by women and girls thereby disproportionately increasing the burden of care and unpaid work on women and girls and at the same time limiting the time spent by women participating in the labour market and economic activities. What is usually not recognised in traditional economic policies is that care and unpaid work are essential in sustaining and reproducing the market economy. Unfortunately, they remain under-recognised and undervalued by the Government and society, and take up a significant amount of women’s and girls’ time and effort, leaving them with less time for engagement in socio-economic activities (ibid).

3.0 Proposed Recommendations and National Actions

3.1 National sensitisation, education and advocacy on the recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry Report

Since the adoption of the 2015 Commission of Inquiry into the Conversion of Insurance and Pension Values from Zimbabwe Dollars to United States Dollars, there has not been any national action or report-back to the general public on the findings and recommendations of the Commission’s Report. There is need for CSOs in collaboration with the trade unions to sensitise, educate and advocate for the implementation of the recommendations from the Commission Report.

3.2 Restructuring national social security systems to integrate the informal economy – Towards a sustainable formalisation of the informal economy

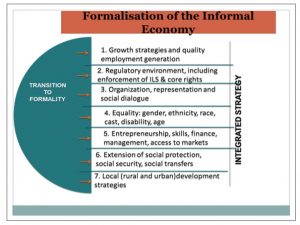

The informal economy has grown substantially, characterised by high social protection deficits yet it is excluded in the existing national social security schemes of NSSA. Hence, there is need for NSSA in collaboration with the informal economy actors and associations to come up with adaptable and innovative social security systems that are appropriate for the informal economy as part of the nation’s formalisation of the informal economy agenda also commonly referred to transitioning from informality to formality (Figure 3).

Figure 3: ILO Framework – Transitioning from Informal to Formal

Source: Adapted from ILO Recommendation No. 204 of 2015

More importantly, transitioning to formality should not be solely based on taxing the informal economy as Vision 2030 proposes, but as indicated in Figure 1 should particularly focus on supporting the informal economy through establishing a regulatory environment that promotes the business, labour, and property rights of the working poor, strengthening social security and the employability of informal workers through skills training and job matching, legal identity and rights as workers, entrepreneurs, and as asset holders for them to gain official visibility in policymaking.

Furthermore, Zimbabwe can learn from international good practices of integrating the informal economy into national social security systems.

3.3 Consolidating fiscal space for investment in social services – Social protection is not a cost but an investment

The existing social protection benefits in Zimbabwe are largely tied to an employment relationship. However, with the expanding informal economy and informalisation of jobs, such a traditional system becomes threatened and increase social protection deficits. A more radical solution would be the application of university principle to social protection provision. This does not necessarily mean putting pressure on the fiscus to finance this scheme. The main challenge for Zimbabwe is not the lack of resources but corruption, lack of stewardship of national resources, resource leakages and lack of prioritisation of social service delivery. The government can strengthen resource mobilisation for social protection by curbing corruption and leakages in the economy and thus unlock resources for social protection and ring-fencing these domestic resources in the national budget to finance a universal social protection guarantee.

According to the ILO (2019), many of austerity reforms have a high human cost and have been found unconstitutional by national supreme courts (Latvia 2009, Romania 2010, Portugal 2013-14). Thus, instead of focusing on cuts, focus should be placed on extending fiscal space for universal social protection at adequate benefit levels.

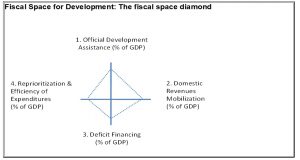

Figure 4, aptly called the fiscal space diamond, hinges on how additional financial resources can be unlocked and mobilized towards high-priority government spending such as investment in employment creation and universal social protection provision. Figure 4 shows the four avenues in which a government can create fiscal space namely Official Development Assistance (ODA), domestic revenues mobilisation, deficit financing and reprioritisation and efficiency of expenditures. Out of the four avenues, Zimbabwean government should concentrate on the two sustainable options namely domestic revenue mobilisation and reprioritisation of expenditures mainly in the national budget.

Figure 4: Fiscal Space Diamond

Domestic resource mobilisation can be enhanced through:

- Improving tax administration, collection, performance, compliance and broadening the tax base in a manner that is progressive;

- Plugging the holes of Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) especially in the context where the former President Mugabe confirmed the missing US$15 billion from the diamond proceeds. In 2015, the Minister of Finance also indicated that Zimbabwe lost US$1,2 billion through externalised funds; and,

- Addressing culture of corruption with impunity haemorrhaging the economy.

Reprioritisation and efficiency of expenditures can be achieved through:

- Prioritising financing Ministries responsible for socio-economic rights (the right to health, social protection, food, education, public utilities, among others). National budgetary allocations should reflect a rights-based approach to development and a thrust towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs);

- Restructuring sectoral budget allocations such that more resources target capital / infrastructure investments as compared to the current scenario where employment costs consume the big chunk of the ministerial allocations leaving little for capital investments; and,

- Rationalizing the size of government, which still remains bloated relative to the size of the economy.

Figure 5 shows country examples on fiscal space strategies for social protection. Zimbabwe can learn from these countries because the State has the overall and primary responsibility ensure these social protection guarantees are met as enshrined in the various international instruments that Zimbabwe has signed to.

Figure 5: Fiscal Space Strategies for Social Protection: Country Examples

Source: ILO, 2019

3.4 Building and Strengthening CSOs and Trade Unions agency on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provides a comprehensive framework for CSOs and trade unions to demand accountability and transparency from the government on its SDGs commitments under the “Leaving no one behind” mantra. SDGs call for integrated and transformative policies to tackle development challenges such as labour, employment and social protection deficits. SDGs also gives CSOs and trade unions the impetus they need to work together to tackle the formidable challenges confronting labour and social protection. In the case of Zimbabwe, the government developed an SDG National Document that prioritised 10 out of the 17 SDGs. Among the priority SDGs are SDGs 5: Gender Equality; SDG 8: Economic Growth, Full and Productive Employment and Decent Work; and SDG 10: Reduction of Inequalities, all which speak directly to the need for comprehensive labour and social protection process for sustainable development.

3.5 Taking labour and social protection issues to the TNF

The mandate of the TNF is to discuss any macroeconomic policy. Hence the restructured of the TNF launched on 5 June ushers a new impetus and new opportunities for the social partners (government, business and labour) to renew discussions and negotiations on developing inclusive, broad-based and comprehensive labour and social protection polies that are transformative in nature. For instance, the current Zimbabwe National Employment Policy Framework is outdated and the new TNF is an opportunity to review this policy through an inclusive process for better outcomes. Furthermore, amendment of the Labour Law, a process that the ZCTU is currently seized with has to be finalised through tripartite dialogues at the TNF.

References

ILO (2019). Financing Social Protection, Paper Presented by Ursula Kulke, Senior Social Protection Specialist, ILO – ACTRAV, Geneva in Windhoek, Namibia, 2-4 May, 2019

LEDRIZ and FES. (2019). Action Research on Social Protection in Post-Independence Zimbabwe, 1980-2019, Harare, Zimbabwe

LEDRIZ and Solidarity Center. (2016). Working Without Pay: Wage Theft in Zimbabwe. Washington and Harare: Solidarity Center.

LEDRIZ. (2016). Situational Analysis of the State of Eight Socio-Economic Rights in Zimbabwe: 1980 – 2016, Harare, Zimbabwe

Sachikonye L. et al. (2018). Building from the Rubble the Labour Movement in Zimbabwe since 2000, Weaver Press, Harare, Zimbabwe

World Bank. (2012). ‘Zimbabwe – FinScope MSME survey 2012’. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

ZimStat. 2004, 2011 and 2014. ‘Labour Force and Child Labour Survey’. Harare: ZimStat.

Download

[wpdm_package id=’947′]