Zimbabwe’s Economy: Restoring Stability and Production

by Kipson Gundani

Acknowledgments

This paper has been authored by Kipson Gundani. The Author thanks all the interviewees who kindly gave their time to discuss the issues in the paper. I gratefully acknowledge the Citizens Convention Organisers for the opportunity. All the views expressed in this paper belong to the author and not necessarily reflect the interviewees or discussants.

BOP – Balance of Payments

CFTA – Continental Free Trade Area

CZI – Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries

FOREX – Foreign Exchange

GDP – Gross Domestic Product

MSME – Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises

RBZ – Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe

RTGS – Real Time Gross Settlement

USD – United States Dollar

ZACC – Zimbabwe Anti Corruption Commission

ZEPARU – Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis and Research Unit

ZNCC – Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce

Executive Summary

Entrenching macroeconomic fundamentals and strengthening capacity recovery requires a marked paradigm shift by all stakeholders – Government, business and labour, in respect of charting a common approach and mutually shared way forward. Several interlocking challenges have combined to stem the tide of recovery and capacity utilization remains in the 30 – 40% territory for most firms. Cash and liquidity, energy and power challenges are among the foremost issues confronting the economy. Inflationary pressures are speedily rising and wage demands are stoking incipient inflation pressures.

High production costs, high costs of borrowing, banking sector vulnerabilities and weak capitalization are attendant and ever present challenges. Debt and arrears continue as an overarching albatross, constraining the economy’s capacity to attract much needed credit lines. Crucially, the way forward demands a coming together of key stakeholders – Government, Business and Labour. The economy requires fresh momentum and clearly the options are narrowly primed.

Government has to recognize that no country can hope to live beyond its means in perpetuity. The unfolding dramatic lessons from our past cannot be ignored. Government has to make difficult decisions to cut back on current spending on a large civil service, on far flung embassies, ghost workers and endless international trips.

Business has to recognize that the era of hyper ventilated profits is no more. Inefficiencies can no longer be cushioned by speculative bubbles and gregarious lifestyles propped up by notional profits, it is not sustainable. Utilities and local authorities have to come to terms with the new reality on the ground, of affordable quality service, of austerity and financial prudence. Customer orientation and service delivery across our value chain has neither civility nor ambiance. Gross improprieties are wrecking the fabric of society and the sense of obligation, diligence and service.

Labour has to recognize that the country is in a unique environment, an uncharted territory, requiring evermore that all stakeholders close ranks and work together to pull the country forward. There is need for a coming together of key stakeholders to agree on critical national imperatives. Industrial action and threats of such action will neither create value and nor enhance the welfare of workers.

An all stakeholder appreciation of the task ahead is critical. Crucially, there has to be a building of trust between Government, business and labour – adoption of a mutually agreed common strategy and an even sharing of the burden. All stakeholders need to share equally the burden of adjustment, to the satisfaction of everyone. This represents the only viable approach.

1. Introduction

Zimbabwe’s economy continues to grapple with fiscal and monetary misalignments, chronic cash shortages, high unemployment (especially among young people), low investment and savings, industrial stagnation, reduced agricultural output. The economy is further troubled by structural challenges from high informality, weak domestic demand, high public debt, weak investor confidence, and a challenging political environment. This crisis is a manifestation of structural deficiencies and distortions in the economy.

The country faces a mammoth task to consolidate the national budget and stabilize the financial sector; stimulating growth and investment to increase revenue collection and foreign exchange generation; protect social gains; and improve governance outcomes through continued legislative and institutional reforms.

The Transitional Stabilization Programme (2018-2020), contains the government’s plans to ensure financial stabilization, stem current liquidity challenges that have seen parallel market exchange rates skyrocket and contribute to inflationary pressures, as well as attract foreign direct investment and improve the balance of trade to boost economic growth. The new administration that began in November 2017, has been championing a Zimbabwe is open for business campaign at the start of its transition, from a publicly-led economy to a private sector-led economy to chart the way to Vision 2030 (an upper middle-class income status by 2030).

In 2015, after a period of recovery (2010 to 2014), Zimbabwe’s economy began a downward trend, that saw a decline in gross domestic product (GDP) growth due to a drought and fall in commodity prices; an expansionary fiscal policy that led to a burgeoning fiscal deficit; rising vulnerability and poverty because of weather and financial shocks; and acute foreign currency shortages dampening demand and supply.

Due to these headwinds, the economy is projected to shrink by 3% in 2019 and may shrink further in 2020. Policy-related macroeconomic instability, the high and unsustainable debt-to-GDP ratio; and inadequate infrastructure (particularly energy), cash shortages, and limited availability of foreign exchange, which continue to constrict economic activity; and the persistent shortage of essential goods, including fuel and consumer goods, remain the major headwinds for any meaningful economic recovery.

1.2. Objectives of the Study

The objective of the study is to give an assessment of the current economic situation in Zimbabwe with a special focus of suggesting solutions to revive macroeconomic productivity. In particular, the study will;

- Give an analysis of the Zimbabwean macroeconomic landscape

- Give a micro analysis of Zimbabwean firms to include level of innovation, creativity, business ethics and renovation of business models.

- Link the informal and formal sectors of the economy and suggest ways of transitioning the informal sector to formal economy.

1.3 Outline of the rest of the study

Section 2 will look at the macroeconomic truths about Zimbabwe. The section will set the context to discuss the probable solutions to restore production and solve the informality question. Section 3 will give an analysis conclusions with recommendations towards restoring economic sanity and production in Zimbabwe.

1.4 Demarcation

The research paper will not include an in-depth study or discussion about the future of the Zimbabwean economy because of the extent of the Zimbabwean economy making it difficult to predict. The paper will not go deep into Zimbabwean politics even though the economic collapse is circled around political actions. The methodology used in this research is qualitative. A lot of secondary data was used is this research, because there has been a lot of discussions about Zimbabwe. Secondary data best suits this research.

2. Zimbabwe’s Macroeconomic Truths

2.1. Economic Growth

A country’s economic growth may be defined as a long-term rise in capacity to supply increasingly diverse economic goods to its population, this growing capacity based on advancing technology and the institutional and ideological adjustments that it demands, Kuznets (1971). Economic growth can also be defined as an increase in the production of goods and services over a specific period. To be most accurate, the measurement must remove the effects of inflation. Economic growth creates more profit for businesses. As a result, stock prices rise. That gives companies capital to invest and hire more employees. As more jobs are created, incomes rise. Consumers have more money to buy additional products and services. Purchases drive higher economic growth. For this reason, all countries want positive economic growth. This makes economic growth the most watched economic indicator.

Zimbabwe’s recovery from decades of economic contraction has largely been shaped by agriculture growth and investment patterns. Zimbabwe had double-digit growth rates shortly after dollarization in 2009, but growth started to decline in 2012 as confidence started to diminish and the investment-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio declined sharply.

The contraction and expansion of the Zimbabwean economy (1980 – 2019)

Figure 1: GDP Growth Rates

Source: Zimstats

The current sluggish growth is expected to endure as government fails to address structural obstacles to growth such as limited capital resource and deficient infrastructure. The economy is expected to shrink by 3% in 2019 on the back of drought effects and energy crisis, Ministry of Finance (2019).

2.2. Fiscal and Monetary Policy

Traditionally, Zimbabwe has twin problems which are trade imbalances (trade deficits) and fiscal imbalances (budget deficits). Zimbabwe’s expansionary fiscal policy that started in 2016 has resulted in unsustainable fiscal deficits that widened from 8.5% in 2016 to 11.1% in 2017 and reached 18 % in 2018.

Consequently, the government financed the fiscal deficit largely through domestic borrowing from both commercial banks and Central Bank using an overdraft facility. The overdraft created electronic deposits or Real Gross Time Settlement (RTGS) in the banking system allowing the government to make payments without concomitant increases in US dollar cash balances. This resulted in a mismatch between US dollar cash balances and RTGS balances and exchange rate weakened while inflation increased averaging 3.1 percent during the first 7 months of 2018 compared to 0.2 percent during the same period in 2017. The expansionary fiscal policy spilled over into the financial sector and resulted in cash shortages that weigh negatively on economic growth.

The 2019 fiscal deficit is estimated to reach ZWL$4.5 billion which translates to an economically acceptable 3.9% of GDP. The government has adopted and is implementing prudent fiscal policy underpinned by adherence to fiscal rules, as enunciated in the Public Finance Management Act, together with financial rules. The reforms also reprioritize capital expenditure through commitment to increase the budget on capital expenditures from 16% of total budget expenditures in 2018 to over 25% in 2019 and 2020.

Yes the government has done well in containing the budget deficit of late but this may not be enough. The economy remains fragile and inflation may cause the deficit to overshoot.

2.3. Production and Capacity Utilisation

A firm’s productive capacity is the total level of output or production that it could produce in a given time period. Capacity utilisation is the percentage of the firm’s total possible production capacity that is actually being used. Thus, it refers to the relationship between actual output that is actually produced with the installed equipment, and the potential output which could be produced with it, if capacity was fully used. Capacity utilisation is calculated as follows:

Capacity utilisation is important for determining the elasticity of supply. If firms are near 100% of capacity utilisation then supply will be very inelastic, at least in the short term. In the long term firms can increase productive capacity and increase the amount of capital. Implicitly, the capacity utilization rate is also an indicator of how efficiently the factors of production are being used. This statistic has been questioned by experts on its ability to deduce the performance of the manufacturing sector. While it remains a key statistic for measuring performance of the industrial sector, it should be noted that capacity utilization should be interpreted together with other statistics such as manufacturing value added, manufacturing output and new investments within the manufacturing sector.

Owing to the positive effects of Import Substitution and Export promotion policies that the Government instituted to support local industry, capacity utilisation increased to 48.2%, which is a 3.1 percentage point increase from 45.1% that was recorded in 2017, CZI (2018). The improvement in capacity utilisation was recorded in the Foodstuffs, Drinks, Tobacco and Beverages, Wood and Furniture and Other Manufactured goods sub groups. Output increased by 12.1% in 2017. In 2018, output increased in tandem with improvement in capacity utilisation. According to CZI, due to the macroeconomic challenges that we are currently experiencing, companies projected capacity utilisation to further decline to 34% in 2019. A very low statistic of 34% for capacity utilisation implies that some companies will not be operating and this means higher unemployment levels in the economy. This results in a vicious cycle as it causes a reduction in aggregate demand which is not good for the companies and the economy in general. This means that Government needs to address the macroeconomic imbalances that are currently prevailing in the economy to ease the doing business environment.

Foreign currency shortages need to be addressed as this was the major challenge that the companies highlighted in the 2018 CZI Manufacturing sector survey. Admittedly, the policies on import substitution that the government put in place are not a panacea to the challenges that the manufacturing sector is experiencing. The doing business environment needs to be addressed in order to improve the competitiveness of the productive sector. The shortage of foreign currency in the economy which is correlated to shortage of raw materials is weighing down on company operations. Local firms need to access foreign currency to import raw materials and intermediate inputs. The main capacity constraints that were recorded in the 2018 CZI survey include:

- High cost and shortage of raw materials,

- Foreign currency shortages

- Antiquated machinery and breakdowns

- High cost of doing business, and;

- Drawbacks from the current macroeconomic environment.

An agreed economic recovery framework that has an integrated plan for across the board costs reduction and increased productivity, more flexible supply side policies, including labour market reforms is critical in stimulating industrial production. The country needs a policy framework that supports enterprise and innovation by reducing bureaucracy and cost of business starts. A policy framework that attracts inward investment and focuses on restoring confidence in the economy. A policy framework drawn from consensus that entrenches and strengthens recovery fundamentals.

2.4. Balance of Payments

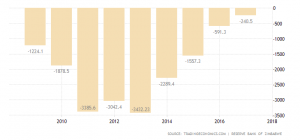

The current account deficit narrowed for three successive years to 2017 partly due to import restrictions and recovery in exports, and these positive signs of recovery extended into 2018 through growth in tobacco, cotton, gold and tourism outputs. The perennial negative balance of trade largely owes to Zimbabwe’s overreliance on imports for basic commodities mainly from South Africa and China. The pervasive current account deficits over the years has caused a BOP crisis resulting in a back log of external payments. The deteriorating trade balance, higher primary income payments relative to receipts and slowdown in transfers, particularly remittances, gave rise to a widening current account balance. Remittances, which make up the greater portion of net income from abroad slowed down to US$1.2 billion in the first three quarters of 2018 compared to US$1.3 billion of the same period in 2017. Consequently, the current account deficit for the first three quarters of 2018 widened to US$935.8 million relative to US$246 million in 2017, giving rise to a negative BOP position of USD240 million in 2018.

Figure 3: Zimbabwe BOP Position ( 2010 – 2018)

2.5. Dynamics and Characteristics of the Informal Sector in Zimbabwe

There is general consensus in Zimbabwe that the economy has tremendously transformed from predominantly formal to informal one since 2000. The focus of this section of the study is on the informal sector, which brings the need for a working definition within the context of this study based on Chen (2012). The informal sector can be defined as production and employment that takes place in unincorporated small or unregistered enterprises. This therefore operates through informal employment, which refers to employment without legal and social protection. This therefore implies that the ability to operate within the legal confines of the law in terms of labour relations and social protection is critical in identifying an informal sector player. It is critical to note that such players can still be registered with the registrar of companies or local authorities, even though they are still informal sector players.

The informal sector has continued to be subjected to a lot of policy discussions and debate, given that the closure and downsizing of companies during the hyperinflationary environment has seen the Zimbabwe economy generally becoming informal. The government has also realised that the informal sector cannot be left out of the policy discourse, which has seen fiscal policy also trying to reach out to the informal economy.

The 2014, 2017, 2018 and 2019 National Budget statements acknowledge that the Zimbabwe economy has undergone significant structural transformation as a vibrant informal sector has emerged, calling for viable mechanisms to mainstream the sector into the development agenda of the country. The 2018 National Budget statement further acknowledges that the current measures put in place to capture the revenue inflows from the informal sector, have not been successful, as revenue contribution to the fiscus from the sector has remained insignificant, thus the justification for the continuation of the 2% intermediary tax introduced in 2018.

The informal sector in general is an important sector of the economy as it acts as a shock absorber for an economy characterised by low growth, unemployment and a struggling formal economy. The ease of entry; reliance on indigenous resources; family ownership of enterprises; small-scale operations and adapted technology makes it possible for the informal sector to survive in environments that the formal sector is struggling. This points at the need for policy discussions and dialogue focusing on the informal sector to be backed by an in-depth appreciation of the realities under which such enterprises operate, for the effectiveness of policy intervention.

The informal sector faces many obstacles in developing countries. These obstacles include; cumbersome start-up procedures, difficulties in accessing electricity, land, finance, and skilled labour, political instability and corruption. But among all these issues, access to finance remains by far the most cited obstacle experienced by firms trying to formalize, grow, and increase productivity. Jerkin (1988) further argued that owing to these characteristics, informal business operators are less likely to enjoy credit from formal lending institutions. This therefore means that they cannot extend credit to their own customers. Informal enterprises usually operate under difficult circumstances, requiring a high degree of flexibility to face changes in key factors of business: availability of raw materials, deficient utilities, price changes and competition

The Finscope MSME Survey of 2012 reveals that about 46% of the adult population in Zimbabwe (18 years and older) are MSME owners. It also reveals that there are close to 2.8 million small business owners in Zimbabwe of which two million (71%) are individual entrepreneurs while about 800,000 (29%) are businesses with employees employing a total of about 2.9 million people. As such, approximately 5.7 million people are working in this sector, thus contributing to employment creation and poverty alleviation. According to the survey, the 2.8 million business owners own a total of 3.4 million small businesses. About 71% comprise individual entrepreneurs (no employees), with 24% operating as micro businesses employing one to five people, while 4% are small businesses employing six to 40 people and only 1% are medium businesses with 30 to 75 employees. The Finscope MSME Survey (2012) estimates that turnover of the informal sector is at least US$ 7.4 billion.

ZIMSTAT (2013) shows that the total value added for the informal non-farm activities was $810 million while the value added from households engaged in agriculture was $921.4 million giving a total $1.73 billion. The ZIMSTAT report showed that about 20% of Zimbabwe’s GDP comes from the informal sector. Organizing the informal sector and recognizing its contribution is critical for economic growth and development. Enhancing the profitability informal sector enterprises will improve the income earning capacity of informal workers; improve their livelihoods; foster financial inclusion, improve legal status, innovation and graduation of the sector into a formalised sector. This could be achieved by allowing better access to financing, and fostering the availability capacity building initiatives and market information for players in the sector.

Uzhenyu (2015) asserts that the informal sector has become Zimbabwe’s largest employer. About 85% are employed by this sector, earning their living together with their families. A number of companies continue to restructure their operations by downsizing leading massive retrenchments and this has resulted in high levels of unemployment in the formal sector. This has seen phenomenal growth of the informal sector in which the jobless are finding reprieve to make ‘ends meet’ as they have families to sustain (CZI, 2014).

Formal sector employment has been shrinking, which means that the character of the Zimbabwe’s informal sector is likely to be inclusive of skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled individuals. Multi-skilling and tasking has now become a key characteristic of persons employed in the informal sector. The skill composition of players in this sector creates a window of opportunity to harness the vast potential that arises from the available skills, knowledge and experience possessed by those offloaded from the formal sector to the informal sector as companies downsized due to the prevailing economic challenges.

Zimbabwe is said to have a high level of literacy of 90.9% (African Globe, 2013) as per the Africa Literacy Ranking 2013 and as such it would be highly unlikely that the informal sector would be dominated by uneducated and unproductive people. An assessment of one of the informal sector markets at Siyaso in Harare seemed to point to a high level of education as most people there indicated that they had at least four ‘O’ Levels (Mpofu, 2012).

Capacitation of players in the informal sector to expand their operations, improve their quality and increasing their access to markets will contribute towards the achievement of poverty reduction and food security for the growing number of workers in this sector. This is so because there are many people informally engaged in small to medium business practice (Uzhenyu, 2015).

The greatest fear among the informal sector players to formalise is the expectation that they would be required to pay taxes, other regulatory and licensing costs without commensurate benefits or incentives accruing to their businesses, ZNCC (2017). The dominant perception in Government’s thrust in the formalisation agenda is the need to expand the tax base to include the informal sector and not so much on incentivising or nurturing the growth of informal sector business to graduate into viable formal businesses.. This explains why the informal sector’s response to the formalisation calls is very slow and low. There is need for highlighting other formalisation advantages to the informal sector players more than the taxation advantages that the government would enjoy whenever government is trying to promote the formalisation agenda.

2.6. Unemployment

The country’s protracted fiscal imbalances have constrained development expenditure and social service provision, undermining poverty reduction efforts. Unemployment pressures have been mounting as employment opportunities continue to dwindle, (Kanyenze et al, 2011).

There are a lot of figures for the rate of unemployment in Zimbabwe doing the rounds, from 95% to 5%, which is surely the biggest range you’ll see for estimates of any indicator. The official statistics from Zim Stats pegs the unemployment rate at 11, 3 % (Zimstats, 2014). Evidently this is not based on the strict definition of the unemployment, but rather considers the multitudes of active people operating in the informal sector gainfully employed. The challenge for Zimbabwe is not the quantum of employment but the quality of employment. Most people would still count as employed under the new ILO standards, but that the majority are employed in the informal economy, characterised by low wages, poor working conditions, little or no social security and representation. Dealing with unemployment in Zimbabwe requires pragmatic measures to put the country back on an industrialisation agenda. The recent cabinet decision to suspend import controls is likely to harm the fragile industry resulting in company closures and more job losses. In his book, Beyond the Enclave, Kanyenze et al argues for a new approach to development in Zimbabwe based on pro-poor and inclusive strategies, which will contribute to the well-being of all of its citizens and wise stewardship of its resources. It offers suggestions on policy formulation, implementation, monitoring and evaluation in all sectors, designed to promote inclusive growth and humane development.

2.7. Debt

Currently domestic debt stands at US$8.8 billion dollars and this presents 3000% growth in domestic debt since 2012. Domestic debt registered a sharp increase from US$4.5 billion in July 2017 to US$8.7 billion in July 2018. The growth was largely driven by expenditure on government subsidies emanating from programmes like command agriculture, Government input schemes and elections related expenditure. In addition to the unsustainably high domestic debt, Zimbabwe’s external debt has increased over the years. External debt grew by 44.2% from US$5.2 billion in 2009 to US$7.5 billion in 2018, giving us a total national debt of US$16.3 billion. This largely owes to the country’s inability to service its arrears, resulting in the continued accumulation of interest charges. This debt distress has rendered Zimbabwe a high risk country and financially unsound economy resulting in dwindling foreign currency inflow and subdued credit lines. The increase in the domestic debt has diverted money from the private sector resulting in low credit creation and subdued productive investments.

2.8. Inflation

Rising money supply, occasioned by budget deficit financing, coupled with foreign currency shortages has seen a surge in inflationary pressures, during the first half of 2018. Official annual inflation rose from 3.5% in January to 4.8% by August 2018, compared to -0.7% and 0.1% during the same period in 2017. Speculative inflation expectations are setting in, further heightening wage review pressures in both public and private sectors.

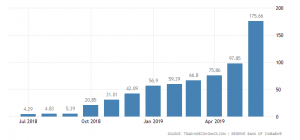

Figure 2: Inflation Rate (July 2018 to June 2019)

Zimbabwe’s year-on-year inflation raced to 175.66 percent in June 2019 from 97.85 percent in May driven by a rise in the price of food and non alcoholic beverages. This comes as a pricing conundrum worsens with business chasing US dollar rates despite government in June formally throwing away multiple currency regime introduced in 2009. The year on year food and non-alcoholic beverages inflation was at 251.94 percent whilst the non-food inflation rate was 143.94 percent. The month on month inflation rate in June 2019 was 39.26 percent advancing 26.72 percentage points on the May 2019 rate of 12.54 percent raising fears that the economy is heading towards hyperinflation again which was tamed by dollarization in 2009. While dollarization improved macroeconomic stability, the economy deteriorated in 2015 with high deficits financed through the issuance of Treasury Bills. Exports steadily rose but Zimbabwe remained generally uncompetitive compared to regional peers due to several factors such as high overheads.

According to the World Bank, hyperinflation is when prices of goods and services rise more than 50 percent a month. During hyperinflation prices will also be rising daily. Zimbabwe is facing the effects of one of its worst droughts in a decade and this has pushed the price of food commodities up as the economy now depend on imports, a trend that is likely to continue due to low production and the weakening of the Zimbabwe dollar. The current power outages which are now lasting up to 18 hours each day are now pushing production costs as many companies in the manufacturing sector are now relying on diesel which is in short supply. Erratic supplies of fuel across the country are also forcing many to buy the commodity on the parallel market where it is being charged in US dollars. Government’s decision to introduce the monocurrency system which replaced the multicurrency system will also have an impact on the inflation outlook of Zimbabwe. Treasury also announced its commitment to settle legacy debts following the monetary reform, a development which will make banks run short of their treasury position.

The Minister of Finance in his 2019 midterm budget review suspended the publishing of year on year inflation figures until the year 2020. This decision is likely to create a void at a time inflation is reality spiralling out of control. The argument by the Minister of Finance, Professor Mthuli Ncube that it’s impossible to calculate inflation because of the change in currency regime from multiple to mono currency is highly challenged. The RTGS existed as the unit of account even in 2009 when we dollarized. Consequently, the National Statistical agency should therefore find no problem in calculating a valid inflation figure.

2.9. Currency Stability and Financial Market Distortions

The parallel exchange rate premiums have been on the rise, particularly from 2018, driven mostly by shortage of foreign currency against rising money supply that is not backed by US dollar cash. This has given rise to speculative demand, as well as induced demand for US dollars as an asset. The eventual pass through effect of rising exchange premiums has been filtered into sudden price increases, particularly on goods. The deepening of parallel market trading is but just a reflection of market corrections, which was inevitably leading towards a second redollarisation in less than 10 years. This was only stopped or delayed by SI142 of 2019 which ended the multi currency regime.

Shortage of foreign currency and cash are not the problem but simply symptoms of the underlying and unsustainable deficits and imbalances over decades. The fact that by our own admission we have broken our own laws through borrowing way beyond legally approved limits should be a wakeup call to us as a country in general and specifically to the Monetary and Fiscal Authorities. The prolonged insistence on an exchange rate of 1:1 and resistance to allow a market determined exchange rate between the RTGS rate and the USD precipitated an effervescence in the economy which dislocated the pillars on which our economy rests.

In 2008/2009, the last time this happened, the Government of the day, did put a dramatic end to the insanity through dollarization and the government went on to compliment this through curtailing government expenditure through “eat what you kill”. It is really regrettable and somewhat embarrassing for us as Zimbabweans to be seeing the same symptoms of 2008/2009 rearing their ugly and smelly heads. This has instantly triggered a raging debate throughout the national on whether we should take the same medicine we took in 2009 and again “dollarize”.

The emergence of parallel pricing structures, sale of cash at a premium, paper currency no longer circulating in banks, no deposits of hard currency into banks, tiered pricing mechanisms have developed. One of the traps we seem to have fallen into permanently is the belief that interventionist measures such as support schemes are the solution to market inefficiencies. The economy has resorted to protectionist and subsidy stance where we think incubating our inefficiencies will wish away the resident challenges currently bedevilling us.

Clearly FOREX generation is NOT the problem. At close to $6 billion in exports, Zimbabwe has enough FOREX, in fact as a country of 16 million people we are punching way above our weight! Kenya a country of 47 million is exporting similar amounts. Zimbabwe therefore, per capita is exporting about 3 times more than Kenya. We have enough FOREX in the country however it is how we are managing or mismanaging our foreign exchange system that we should address.

2.10. Corruption and Moral deficit

Apart from fiscal and monetary factors, Zimbabwe is haemorrhaging from serious moral deficit that has been shaped by bad economic governance over the years. Zimbabwe is the 160 least corrupt nation out of 175 countries, according to the 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index reported by Transparency International. Corruption Rank in Zimbabwe averaged 123.48 from 1998 until 2018, reaching an all time high of 166 in 2008 and a record low of 43 in 1998, meaning Zimbabwe has increasingly become more corrupt over the last 20 years. According to Afrobarometer and Transparency International’s 10th edition of the Global Corruption Barometer, 60% of Zimbabweans think that corruption levels have increased in the past 12 months. Seventy-one percent think that the government is doing a bad job in fighting corruption, while 25% of public service users paid a bribe in the past 12 months and 45% think the general public can make a difference in the fight against corruption.

According to the survey, overall bribe rate has increased from 22% in 2015 to 25% in 2019. Other key institutions that have been dogged by corruption include public schools, public clinics and health centres, identity documents procurement and the police. There is there low confidence on the current crack down by ZACC on the sincerity of government to fight the endemic scourge of corruption.

2.11. Innovation and Creativity

The industrial revolution was primarily the result of ideas. People and business leaders found innovative ways of adopting technology and making it commercially viable so that it could boost productivity. In a world where labour and capital are quite mobile, the main explanation of economic differences between rich and poor countries is not just money, it is also and increasingly the difference in their ability to generate, or borrow and use the best ideas out there.

Zimbabwe has investment opportunities requiring minimal additional investments to realise medium term growth targets. Deep structural reforms can improve Zimbabwe’s business environment and attract private investment and the return of skilled labour. In particular measures are required to increase transparency in the mining sector, strengthen property rights, reduce fears of expropriation and control widespread corruption.

With the generous endowment of natural resources, existing stock of public infrastructure and comparatively skilled labour force, Zimbabwe has an unprecedented opportunity to join existing supply chains in Africa via the Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA).

3.Conclusion and Recommendations

- Zimbabwe has opportunities requiring minimal additional investment to realize medium-term growth targets. In particular, measures are needed to increase transparency in the mining sector, strengthen property rights, reduce expropriation concerns, control corruption, and truly liberalize the foreign exchange markets. Regeneration of civil society and a renewed engagement with political actors in a positive social contract will accelerate political reform. Given the vast natural resources, relatively good stock of public infrastructure, and comparatively skilled labour force, Zimbabwe has an opportunity to join existing supply chains in Africa through the Continental Free Trade Area. To take advantage of such opportunities, the government has adopted a three-pronged strategy based on agriculture, ecotourism as the green job generator, and special economic zones, growth pillars anchored on enhanced economic and political governance.

- It must be said that the relationship between money supply and budgeting is also causing untold difficulties for Zimbabweans. As a country we have tended to grow money supply with near recklessly abandon. This lack of fiscal discipline has put phenomenal inflationary pressure on the demand

- Zimbabwe should not be a leaking bowel where on one hand we are scuppering for investment which at the same breath we are losing the investments we already have. For developing countries like Zimbabwe, whose economies depend heavily on natural resources, it is critical to apply the rents generated from natural resources to facilitate diversification to other non resource based industries. Priority sectors should be compatible with a country’s endowment structure and comparative advantages.

- The above critical components for successful economic policy are interrelated and mutually reinforcing. Macroeconomic policy credibility is an integral aspect of any successful economic recovery package, particularly determining the public confidence and their belief in the economic policy measures. To resolve the credibility deficit currently obtaining, there is need for considerable building of public confidence. The public had generally viewed macroeconomic policy with deep suspicion following the recent experiences. Economic recovery would thus be premised on persistent application of consistent, coherent, well planned and effectively coordinated recovery policies, implemented as a total package – an integrated set of well sequenced macroeconomic recovery measures.

- Dialogue Matters – Clear diagnosis of causes and symptoms

The starting point of the dialogue series would be a clear diagnosis of causes and symptoms. Many times, when the economy has been subjected to challenges over a protracted period of time, the attendant difficulties can pervasively impair the understanding of causes and symptoms. Policymakers may run the risk of transposition – treating symptoms as causes and vice versa. It is, therefore, necessary to clearly identify and separate causes from symptoms.

- Any economic reform programme should therefore be designed to deal with the underlying causes and the symptoms will progressively disappear as the policies become entrenched and take effect. The programme of reforms is premised on the foundations of genuine broad-based stakeholder buy-in. The approach is critical for effective synergies across all the various stakeholders; Government, Business and Labour, but also including local civic organizations and the population at large. Stakeholder buy-in cannot always be quantifiable but the effects are readily discernible. The absence thereof is marked by apathy, distance and preponderance by those feeling excluded to standby in detached indifference. The presence thereof creates an infusion of fresh energy, visible passion, unleashing a national synergy, for economic recovery.

- Institutional Reforms

Focus on institutional reforms, particularly local authorities, tariff realignment and public enterprises restructuring. Public enterprises restructuring particularly focuses on the twin objective of service delivery and financial viability. The framework envisages comprehensive public enterprise reforms to increase operational efficiency and eliminate dependence on the fiscus.

- The Growth Model

Zimbabwe should come up with a model that promotes the growth and development of the economy. The Zimbabwe growth model can be any one or a combination of the following:

- Targeting a specific sector such as agriculture, mining or manufacturing as the anchor for economic growth;

- The promotion and development of the export sector; and

- The development of the SME sector as the anchor for economic growth.

4. References

AFDB (2013). Recognizing Africa’s Informal Sector. http://www.afdb.org/en/blogs/afdb-championing-inclusive-growth-across-africa/post/recognizing-africas-informal-sector-11645/

Chen M A (2012). The Informal Economy: Definitions, Theories and Policies. Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Working Paper No. 1, Cambridge.

Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (2018). 2019 National Budget Statement Austerity for prosperity, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Harare

Government of Zimbabwe (2017). Statutory Instrument 122 [CAP 14:05 control of goods (Open General Import Licence)(amendment) Notice 2017 (No.5)]

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (2018). Monetary Policy Statement Enhancing Financial Stability to promote Business Confidence, Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, Harare

ZEPARU (2016). Identifying Suitable Funding Models for the Informal Sector in Zimbabwe. http://www.zeparu.co.zw/en/dowloads

ZNCC (2018). Understanding the Dynamics of the Informal sector in Zimbabwe. http://www.zncc.co.zw/research

ZIMSTAT Trade Statistics data

http://compare your country – org/trade-facilitation